Tempestuous Elements

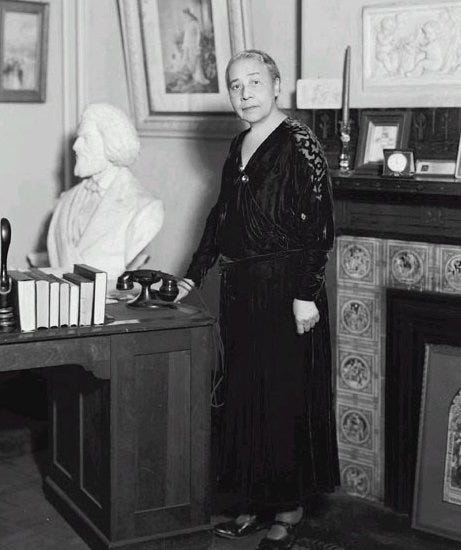

The Legacy of Anna Julia Cooper

“I would beg …for the Colored Girls of the South–that large, bright, promising fatally beautiful class that stand shivering like a delicate plantlet before the fury of tempestuous elements, so full of promise and possibilities, yet so sure of destruction… the hope in germ of a staunch, helpful, regenerating womanhood on which, primarily, rests the foundation stones of our future as a race.” -Anna Julia Cooper, “A Voice From the South,” 1892

After discovering Anna Julia Cooper a few years ago, I have been dedicated to reading everything I can about her life and absorbing as much as possible from her talks and essays. Anyone who proposes classical education in America without considering her arguments and example is missing a vital piece of the story (See this recent forum on “What is Classical Education?” to which I contributed).

Anna Julia Cooper was born a slave (1858) and went on to become the fourth African American woman in history to earn a PhD (at the Sorbonne). Her life was dedicated to education, specifically classical education, and in particular for African Americans. Having completed Latin and Greek studies as an undergraduate, followed by a Masters in mathematics, Cooper taught at M Street High School, a Black public school with a Black superintendent (which is important for the story of what happened next for Cooper). She was promoted to principal of M Street (later called Dunbar High School), but after four years as its leader was ousted by the newly appointed white superintendent, Percy M. Hughes. Her students were outperforming white students and receiving more scholarships to Harvard, Yale, and other elite colleges. She was asked to reduce her classical curriculum to a Black course of study modelled more on the Tuskegee Institute: woodworking, sewing, business classes, rather than calculus and translating Virgil.

The classical education that Cooper offered her students was being derided. When she was asked, “What good is this education for the Negro?” Cooper answered:

“The aim for education for the human soul is to train aright, to give power and right direction to the intellect, the sensibilities and the will.”

Her courageous revolt to uphold a classical education for her curriculum paid off, at least for her students. The compromise seems to have been removing Cooper and retaining her beloved curriculum. The “M Street Controversy” (1905) was the subject of the 2024 play “Tempestuous Elements” performed at Arena Stage in Washington, DC.

I flew to DC from LA for one day (less than 24 hours) for the opportunity to see the play of this figure that I so admire. While the play itself was a letdown (one of my fellow attendees said it was like watching someone read Wikipedia articles aloud), it was still worthwhile to feel as though Cooper was coming to life before me. Here was a woman that history books forgot, that my education had never placed front and center, and here she was commanding a stage in the twenty-first century.

The most captivating moment was when Cooper has just heard some distressing news regarding her position as principal, and a young girl comes to her office to practice her recitation of lines from The Iliad. The student will be performing Hecuba, who cries out against the “madness” that surrounds her. Cooper teaches the girl how to feel what Hecuba would have been experiencing and translate the emotion into her recitation of the poetry. In this moment, observers connect Cooper’s distress over the Board’s decision with Hecuba’s cry against Priam, “Where have your wits gone?” (Wilson’s trans. Book 24.191). The playwright trusts the audience to draw the correlation between the recitation, the meaning in Iliad, and the insanity assaulting Cooper.

If only all of the play had placed such confidence in the viewer. More needs to be done on Cooper’s life and her rebellion against those who attempted to deprive “her race,” as she writes, from ennobling education. More need to follow her example—including Homer in high school reading lists, encouraging students to recite poetry, expecting the next generation to study Latin before college.

As we imagine education for the future, we do well to consider the best examples of education from the past. Among which, Anna Julia Cooper stands as a beacon of light.

Recommended Links:

My book club on Homer’s Odyssey and Iliad are available on YouTube. Also, I recently recorded a conversation with Dcn. Garlick on Book XV of Iliad for his podcast, Ascend, coming out soon.

Shirley Moody-Turner is writing an interpretive biography of Cooper, so be watching for that. Her collection of Cooper’s essays and letters is available from Penguin. I just taught “A Voice from the South” in my Great Books class at Pepperdine.

Flannery O’Connor’s Why do the Heathen Rage? was featured in the New Books podcast.

I returned to the Strong Women podcast to discuss Reading for the Love of God.

I’m currently reading Lucy S. Austen’s biography of Elisabeth Elliot, which is well done—even if I regularly close the book and complain to my husband about Elliot’s theology. Here is Thomas Kidd’s review of it.

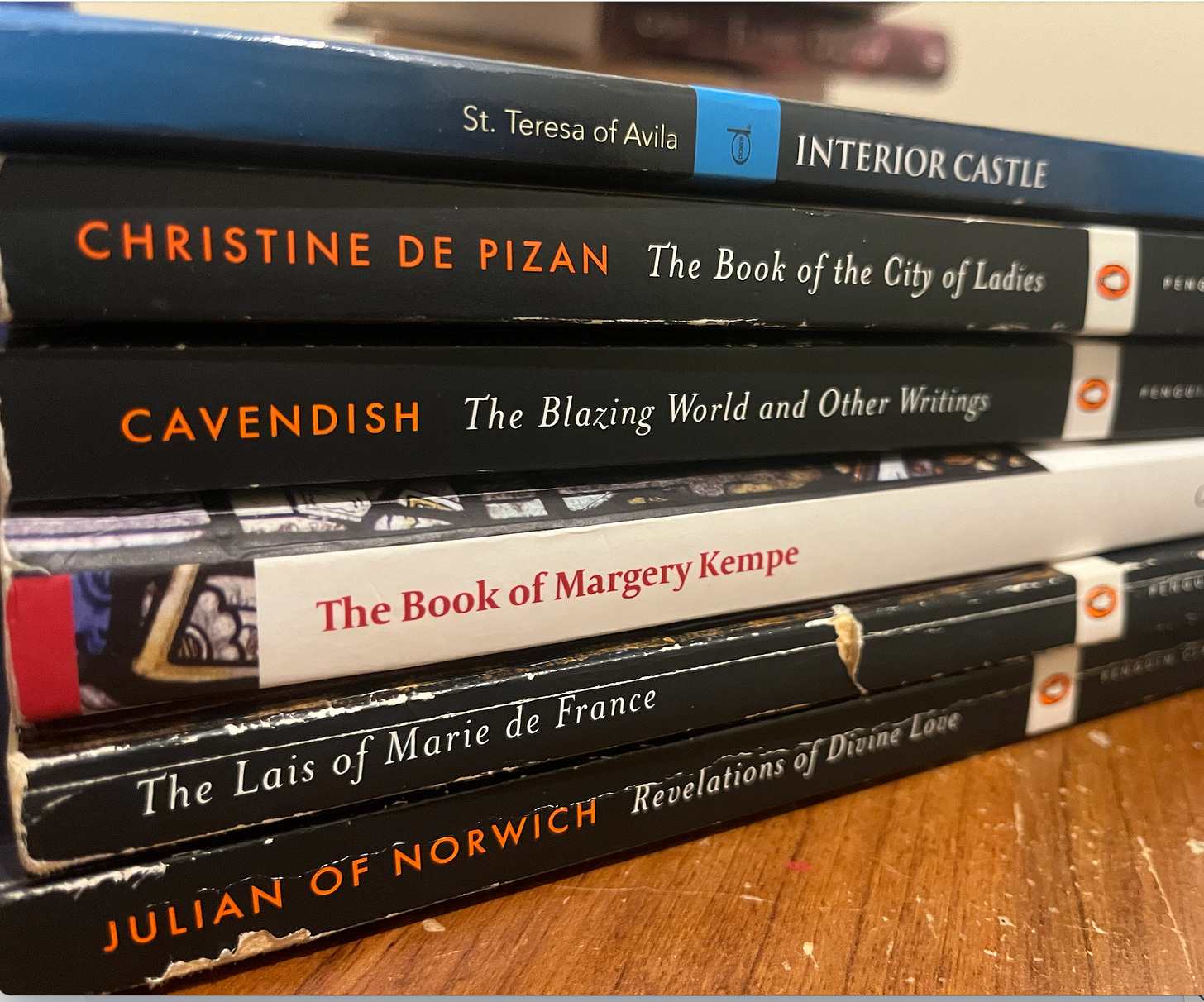

This summer (May-June) I’m teaching in Switzerland at Chateau d’Hauteville, a castle that Pepperdine owns. I’ll be there with my family, teaching students about women writers in Europe (1000-1700). Here’s a pic of the castle and our reading list.