Reading Frankenstein

God the Creator and His Curious Compassionate Creatures

When Victor Frankenstein imagines creating a human being, he undertakes the task seemingly in imitation of the divine. “A new species would bless me as its creator and source; many happy and excellent natures would owe their being to me. No father could claim the gratitude of his child so completely as I should deserve theirs,” Frankenstein recalls. This hope that Frankenstein expresses is to be “creator” and “source” and “father,” titles for God. One of my students assumed, after reading this description, that Frankenstein acknowledges a “paternal duty” toward the creature.

But I had to point out that Frankenstein sees the creator-creature relationship as one directional: the creature would “owe” its being to Frankenstein, who would be due its “gratitude.” Why do we assume that the creator owes anything to the created? After all, the creature has been gifted life without first meriting it. Frankenstein, who appears to be imitating God, but is in fact parodying God, expects blessing and praise. He never considers responsibility or duty. In this misunderstanding of God lies Frankenstein’s initial undoing.

Without Frankenstein stewarding his creation, caring for its upbringing, or securing its belonging in the world, the creature becomes an untethered Adam who forges his own path through the world. Instead of knowing the creator in whose image he is formed, this creature parrots an exiled family in the woods, retaliates to violence with violence, and chooses vengeance against the creator that abandoned him.

The assumption that the Creator owes his creature any paternal duty comes from our Christian hangovers, in which the world once believed in God as the Creator who was good; saw his creation as good; loved the world so much that He gave his one and only Son to redeem it from the cross. But by 1818 when Mary Shelley is writing her novel Frankenstein, this Christian God of goodness and love has been dissected and discarded.

For the Romantics, Satan is the hero of Milton’s Paradise Lost and its in his image that they create. Frankenstein more closely imitates Satan in overreaching for power and in misunderstanding the Almighty. When the monster finds a book in the forest, Paradise Lost, he reads it and identifies with the image of himself in Satan. While the creature realizes that he could have been like Adam “come forth from the hands of God a perfect creature, happy and prosperous,” he found himself “wretched, helpless, and alone” with Satan as “the fitter emblem of my condition.” It is Frankenstein’s lack of virtue, his dearth of goodness and humility, that created something Satanic in his own image. No one is surprised then when the monster determines, like Satan, “Evil be thou my good.” What other telos could he have with his source in Frankenstein? “In my beginning is my end,” as T.S. Eliot once wrote.

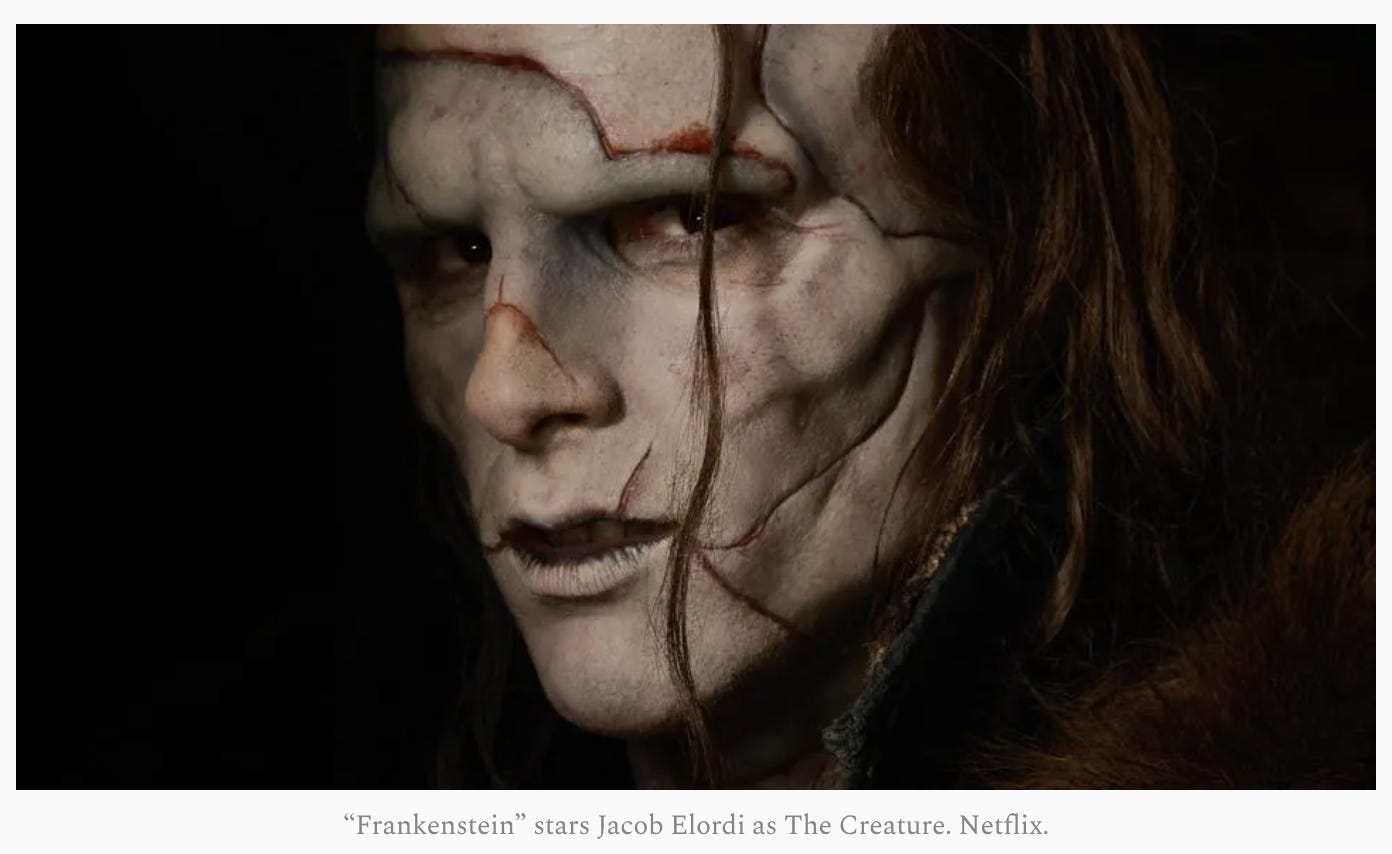

The current film adaptation by Guillermo del Toro emphasizes Frankenstein’s demonic disposition (see Matthew Smith’s review here). He stoically chooses body parts from men about to be hanged, while they still are alive. From the wreckage of a battlefield, he picks out more pieces from corpses. I turned away and shut my eyes when Frankenstein actually stripped apart the bodies and sewed them into one whole, but the refuse that Frankenstein jettisons should have been buried, should have been treated with reverence for the human being. The image of Frankenstein bagging up carcasses for the trash reminded me too much of the mass graves in the Holocaust.

Although the novel depicts Frankenstein as a Romantic desiring to create life, in the film version, Frankenstein wants to overcome death by discovering immortality, which he accomplishes. The film then threads together the Romantic impulse, which seems good—creating and life giving, with its dangerous potential end—immortality apart from its source in a good God. Without God, the human being is fully autonomous, and the potential for evil is limitless. Without God, all other human beings are disposable matter.

Rather than review the film, let me conclude with a bit of hope from the novel’s frame narrative (that is hinted at in the film). An explorer of the Arctic Walton has the same self-aggrandizing temptation of the young Frankenstein; he writes letters to his sister in Britain about his aspirations for immortal glory while the men of his ship grumble and long to return home. You notice when reading that Walton complains of loneliness and friendlessness (while writing to his sister! and surrounded by sailors!). The situation matches the early Frankenstein who took for granted the people around him.

After being compelled to listen to Frankenstein’s story before the wretched scientist dies, Walton changes. The alteration has not occurred because of any advice or wisdom from Frankenstein—who actually is inconsistent and never admits any fault or regret in his accounting of what happened. But when the monster boards the boat unwelcome, Walton approaches him without disgust but with kindness. He asks him a question, and they converse. Walton does not fulfill Frankenstein’s final wish and kill the creature, but he permits him to go. Then Walton surrenders to the will of his men, relinquishes his scheme for glory, and sets sail for home.

The novel describes Walton’s approach of the monster as full of “curiosity and compassion.” In the first virtue of curiosity exists humility that Frankenstein lacked. His curiosity was curiositas—a vice—because it was excessive and unbounded. Whereas Walton humbly seeks to know the creature. A question is an act of humility; it presumes to not know. Also, compassion means suffering with, a virtue that Frankenstein never attempted. He never empathized with the creature or attended to his suffering. How did Walton acquire curiosity (the virtuous kind) and compassion over the course of the novel? By patiently listening to the story that Frankenstein shared and feeling with the storyteller. The actual absorption of the story altered this character from a monologic letter writer and unfeeling captain to a dialogic conversant who leads in communion with his men.

We have three options in the novel for how then shall we live: Frankenstein, his monster, or Walton. While the latter never gets much airplay, Walton has the most in common with us the readers. Frankenstein and his creature were mirror images of one another. Unless we want to see their reflections in us, we should choose to image Walton in our lives—by choosing curiosity and compassion.

What I’ve Read Lately

This book is not about rights and privileges for women but more essentially about protection. The author writes boldly for why she cares for women and why we should too! I found it charitable and bold and a worthwhile read, especially for now.

I’m late to the party for the Rachel Held Evans’s posthumous book Wholehearted Faith (with Jeff Chu) which was a NY Times Bestseller, but I loved how she claimed that her faith relied on the testimonies and witnesses of women. We have such an emaciated imagination when it comes to women’s examples in the faith, and Evans begins her book with a litany of women who said Yes to God. “I am a Christian because of women who showed up,” Evans proclaims. She gives Mary back to Protestants: “God trusted God’s very self, totally and completely and in full bodily form, to the care of a woman,” and God “needed a woman to say: ‘This is my body, given for you.’” It’s a beautiful book full of honest wisdom.

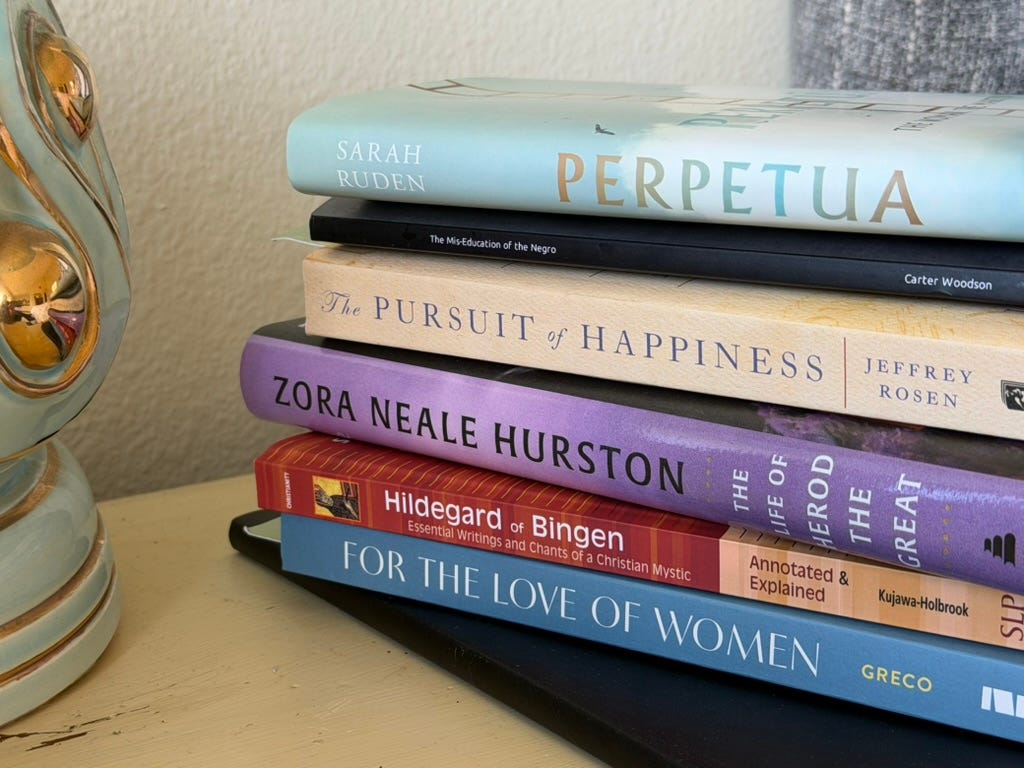

I also read Jesus Feminist, finished listening to Nancy French’s Ghosted (both of which I give five stars), and I’m looking forward to reading a stack of books over the holidays.

Read The Tempest

You may be feeling frustrated with the technology take over (I can’t even go without my phone on Sunday any more because the nursery at church needs to text me to drop off my toddler). My antidote: read The Tempest. Check out my conversation with Curtis Chang on our recurring segment “Reading to Make Sense of the World.”

I presented at the Christy Awards Gala on November 7. Congratulations on all the winners!

And I spoke at chapel at Montreat College and gave a lecture there. You’re welcome to watch—I talked about how Jesus gives us the eyes to see and the road to Emmaus (Luke 24).

While the world goes crazy, I hope you spend your Thanksgiving holiday focused on the things that you’re grateful for. Here’s a piece I wrote five years ago about Gratitude as a Virtue. May it bless you!